My custom LaTeX styles

By popular demand, my custom LaTeX styles are now available for download. (All of them have been dedicated to the public domain, I disclaim all copyright.)

There are four for now, but the set will grow. The first lets you use OpenType fonts (which is pretty much any system font); the limitation is that this works only with a single distribution, XeTeX, available only for Mac OS X, and a new experimental build for Linux. A second style typesets all chapter titles, sections, subsections and subsections in a sans-serif font (instead of the default serif). Very effective when used in conjunction with the OpenType style.

The final two adjust margins to require less paper for draft prints and such. Be good, be green.

One-button Phone Number Sharing

How often have you found yourself calling a friend to get the phone number of a mutual friend? And then having to hold the phone while your friend pulls up the contact list on their phone, then recites the number to you, and then you write it on paper because your phone won't let you add contacts while you're on a call, and then you misplace the number you wrote on paper, ad nauseum. Why isn't there a single button that says "Send this Phone Number to the Current Caller"?

It's a common problem. You're out and about, and realize you need to call a specific person, but you don't have their phone number (or more often, you have it on your desktop computer, or your laptop, but that doesn't do you any good in the current situation.) So you decide that the best thing to do is to call a mutual friend and ask them.

When they receive a phone call from you, they're fumbling to hold the call while they look in their address book. (That is, if they're lucky, and if their phone actually lets them open the contact list while they're on a call.) More often, what happens is that they tell you to hang up while they consult their address book. And then you have to hunt for a piece of scrap paper because your phone won't let you add a number to the list like that.

What the world needs is a button next to each phone number in the contact list that only appears whenever you're on a call. The button, when pressed, sends an SMS from you to the current caller, and contains within it the information from the contact record you just selected. It doesn't have to be too fancy, a two-line VCF record should do nicely.

If the recipient's phone understands this method of contact transfer, it can prompt the user and import it automatically. If not, the user can still read the SMS herself, and dial the number. No more paper, no more fumbling, no more "let me call you back".

It's so easy, a caveman could do it. If only phones implemented it!

My Research Philosophy

I wrote this recently, not as a blog post, but for another purpose. I figured I'd post it here like I do everything else.

Re•search: noun. Investigation or experimentation aimed at the discovery and interpretation of facts, revision of accepted theories or laws in the light of new facts, or practical application of such new or revised theories or laws.

—Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

The last part of that definition has always been the chief motivator for me in my research — practical application. While all research seeks to discover universal truths and deeper meaning, I strongly believe that researchers have a responsibility to contribute to society in other tangible ways as well.

Just as Gutenberg's invention of the printing press in 1439 made literary works accessible to everyone, the Internet is likewise speeding up the propagation of knowledge now and will continue to do so in the decades to come. We are on the brink of a cultural revolution where ideas, prototypes, discussion and research know no boundaries of location or time. The Free Software Movement is promoting users' freedom to understand and explore computer programs. The Creative Commons project encourages authors, scientists, artists and educators to distribute their creations under licenses that foster the sharing of ideas, encourage discussion, engender a culture of openness, and speed up innovation. This provides enormous opportunities for researchers to collaborate in real-time across institutions, countries and continents, and to serve the community by disseminating their research results via public blogs, videos, slides, prototypes and designs.

As a researcher in Human-Computer Interaction at the Dept. of Computer Science at Virginia Tech, I have developed several tools and prototypes that would be of benefit not just to researchers but also to computer users. It is by studying their habits that I designed these tools — to them, I owe these tools. I work in the area of Personal Information Management (PIM), and study how users access and manage information such as files, calendars, email messages, contacts and bookmarks on multiple devices. I release all such tools and software to the world at my web site under licenses that permit anyone to inspect the source code, build upon it, and benefit from it.

In the process of my research, I developed a program to access Google Calendar which now has over 25,000 users. A calendar converter program I wrote is used by an average of more than 200 users per day. During Sustainability Week 2008 at Virginia Tech, I released a Blacksburg Transit Schedule application for cell phones to encourage Blacksburg citizens to take the bus instead of driving. It is used by about 300 users every month and growing.

In the spirit of working on real products that are used by real people, I interned at Google three times during my Ph.D. (2005, 2006, 2007.) In 2007, my project enabled users of Google Book Search to clip personalized content from books and embed that into their own web site or blog. This enables teachers to excerpt from literary classics for their class home page, for literature scholars to debate the nuances of texts, and for commentators to dissect parts of books. My intern work was covered by several news outlets, chief among them, at Google's Corporate Blog.

Academia encourages published work—publish or perish, they say—while original contributions such as new ideas and untested directions are undervalued in the traditional ways of evaluating research. The Internet changes that too. Several times when I have come up with ideas that may or may not be viable research projects, I have written about them on my blog. The public scrutiny and invaluable feedback I've received made it easy to separate the wheat from the chaff. My advisor has always been supportive of those ideas that were encouraging research directions: the latest among them resulted in a paper that has been nominated for the ACM SIGCHI Student Research Competition 2009.

An area that I have recently been concerned about is the open publication of raw data sets. I perform human experiments which are reviewed by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) for ethical compliance. There is inherent tension between the privacy implications of human experiments and the Open Science dream of being able to publish all experimental data publicly so that others may analyze it in novel ways. I plan to investigate the ethical, moral and legal responsibilities of such an endeavor, recognizing that we as researchers owe two allegiances: to our experiment participants and to the scientific community, in that order.

I am happy to be a researcher at a time in our history when competitive collaboration trumps closed confidentiality. Science and innovation can only progress faster when information is freely shared among researchers, scholars and citizens.

10th Anniversary of my First Shareware Paycheck

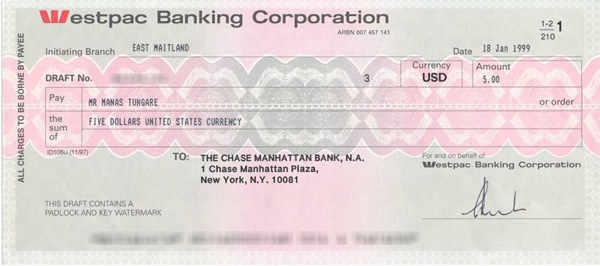

10 years ago, on this day, I received the first payment for a tiny shareware program I wrote. It was a one-trick-pony, a birthday reminder program.

Folks around me will tell you I'm bad at remembering things, and always choose to write everything down. So I wrote a program to keep track of friends and birthdays, and popup a reminder on the right day, perhaps a few days earlier if I needed to buy a gift first. As a teen writing and distributing my first-ever commercial piece of software, I had named it eponymously as ManasTech Birthdays. I wrote it, released it, and sold a few copies (nothing astronomical, but yeah, it was fun to see the checks coming in.)

As I look back nostalgically, several thoughts cross my mind today. The more things have changed, the more they have remained the same. I loved writing software then, I love writing software now. I used to sneak out of classes and stay up late nights to code up the latest idea that crossed my mind. Today, I procrastinate on my research and take time off to write little scripts and tiny widgets, that -- before you know it -- have hundreds of users and need regular maintenance.

Then, the norm was to release products as shareware, without the hassles of finding a publisher or having to stock shelves with packaging. All you needed was an Internet connection and a program that solved a need. Today, the norm is to free your software, and release it into the wild. The Free Software Movement has been gaining ground ever since.

The most interesting aspect is perhaps the domain in which I've been working. The Birthday Manager helped store your personal information -- contacts and calendar events. Today, I'm involved in Personal Information Management research, which is pretty much the same topic. I even wrote a paper detailing how people manage their calendars. Little had I known 10 years ago that I would be fascinated enough with personal information to pursue a career in it.

Sometimes I wonder what the next 10 years will be like.

Update: P.S. For those curious about how I got hold of the check image for this blog post: yes, I'm a digital packrat and have a copy of all my files dating back to 1997 on my current laptop.

HOWTO Make your Mac speak over the Web

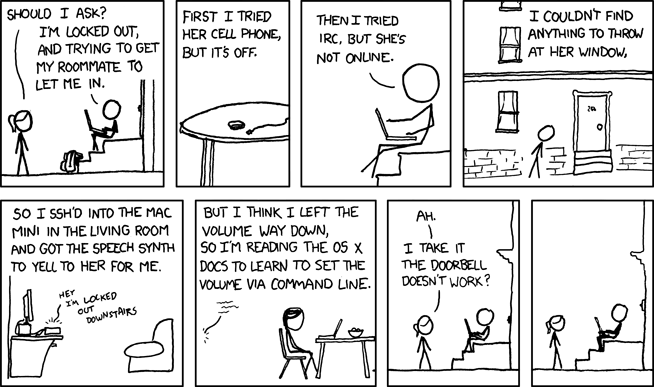

Randall Munroe's XKCD has inspired interesting product features in the past. A recent one has sent a lot of Mac users scurrying to set up an audio doorbell on their Mac Minis.

Here's how you can do it.

The Source Code